Abacus is an ancient tool used invented to perform mathematical operations. It is still considered to be the most powerful calculating device, but can only be used by a trained abacus person. The definite origin of the abacus is obscure, there is some reason for believing that its earliest form was a reckoning table covered with sand or fine dust, in which figures were drawn with a stylus, to be erased with the finger when necessary.

The English word abacus is etymologically derived from the Greek abax, meaning a reckoning table covered with dust, which in turn comes from a Semitic word meaning dust or a reckoning table covered with dust or sand. In time this sanddust abacus gave place to a ruled table upon which counters or disks were arranged on lines to indicate numbers. Various forms of this line abacus were in common use in Europe until the opening of the seventeenth century. In rather remote times, a third form of abacus appeared in certain parts of the world. Instead of lines on which loose counters were laid, the table had movable counters sliding up and down grooves.

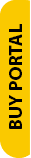

All three types of abacuses were found at some time or other in ancient Rome —the dust abacus, the line abacus, and the grooved abacus. Out of this last type yet a fourth form of the abacus was developed—one with beads sliding on rods fixed in a frame. This form, the bead or rod abacus, with which calculations can be made much more quickly than on paper, is still used in China, Japan, and other parts of the world. In Europe, after the introduction of Arabic numerals, instrumental arithmetic ceased to make much progress and finally gave way altogether to the graphical as the supply of writing materials became gradually abundant.

As for the Orient, a form of the counting-rod abacus, called ch’eou in China and sangi in Japan, had been used since ancient times as a means of calculation. The Chinese abacus itself seems, according to the best evidence, to have originated in Central or Western Asia. There is a sixth-century Chinese reference to an abacus on which counters were rolled in grooves. The description of this ancient Chinese abacus and the known intercourse between East and West give us good reason to believe that the Chinese abacus was suggested by the Roman. The Chinese write in vertical columns from above downwards. If they ever are compelled to write in a horizontal line, they write from right to left. But the abacus is worked from left to right. This is another indication that the abacus was not indigenous to China. The present Chinese bead abacus, which is generally called suan-pan (arithmetic board) in Mandarin and soo-pan in the southern dialect, was a later development, probably appearing in the twelfth century, and did not come into common use till the fourteenth century. It is only natural that the people of the Orient, having retained a system of numerical notation unsuited for calculation, should have developed the abacus to a high degree, and its continuous universal use even after the introduction of Arabic numerals is eloquent testimony to the great efficiency achieved in its development.

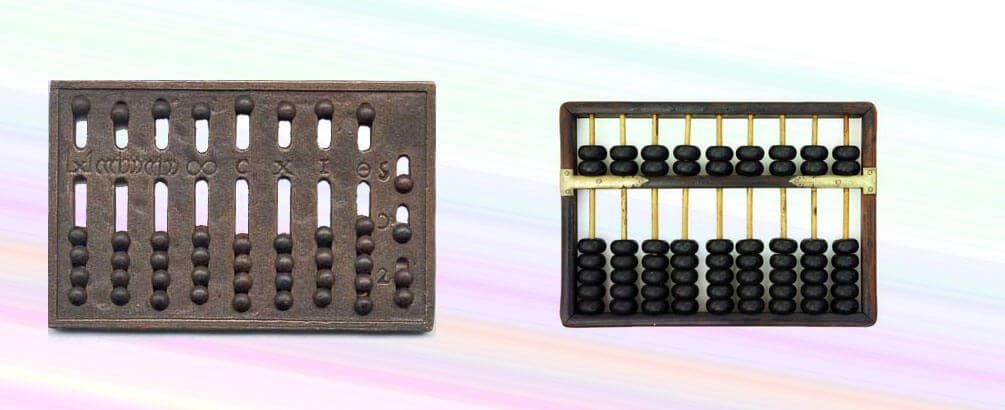

The Japanese word for abacus, soroban, is probably the Japanese rendering of the Chinese suan-pan. Although the soroban did not come into popular use in Japan until the seventeenth century, there is no doubt that it must have been known to Japanese merchants at least a couple of centuries earlier. In any case, once this convenient instrument of calculation became widely known in Japan, it was studied extensively and intensively by many mathematicians, including Seki Kowa (1640 — 1708), who discovered a native calculus independent of the Newtonian theory. As a result of all this study, the form and operational methods of the abacus have undergone one improvement after another. Like the present-day Chinese suan-pan, the soroban long had two beads above the beam and five below. But toward the close of the nineteenth century it was simplified by reducing the two beads above the beam to one, and finally around 1920 it acquired its present shape by omitting yet another bead, reducing those below the beam from five to four. Thus the present form of the soroban is a crystallization of labor and ingenuity in the field of Oriental mathematics and science. We feel sure that the soroban, enjoying widespread use in this mechanical age on account of its distinct advantages over the lightning calculating machine, will continue to be used in the coming atomic age as well.